Marlborough is pleased to present a solo exhibition of new paintings, recent found-painting interventions, and a career-spanning pair of sculptures from the German artist Werner Büttner.

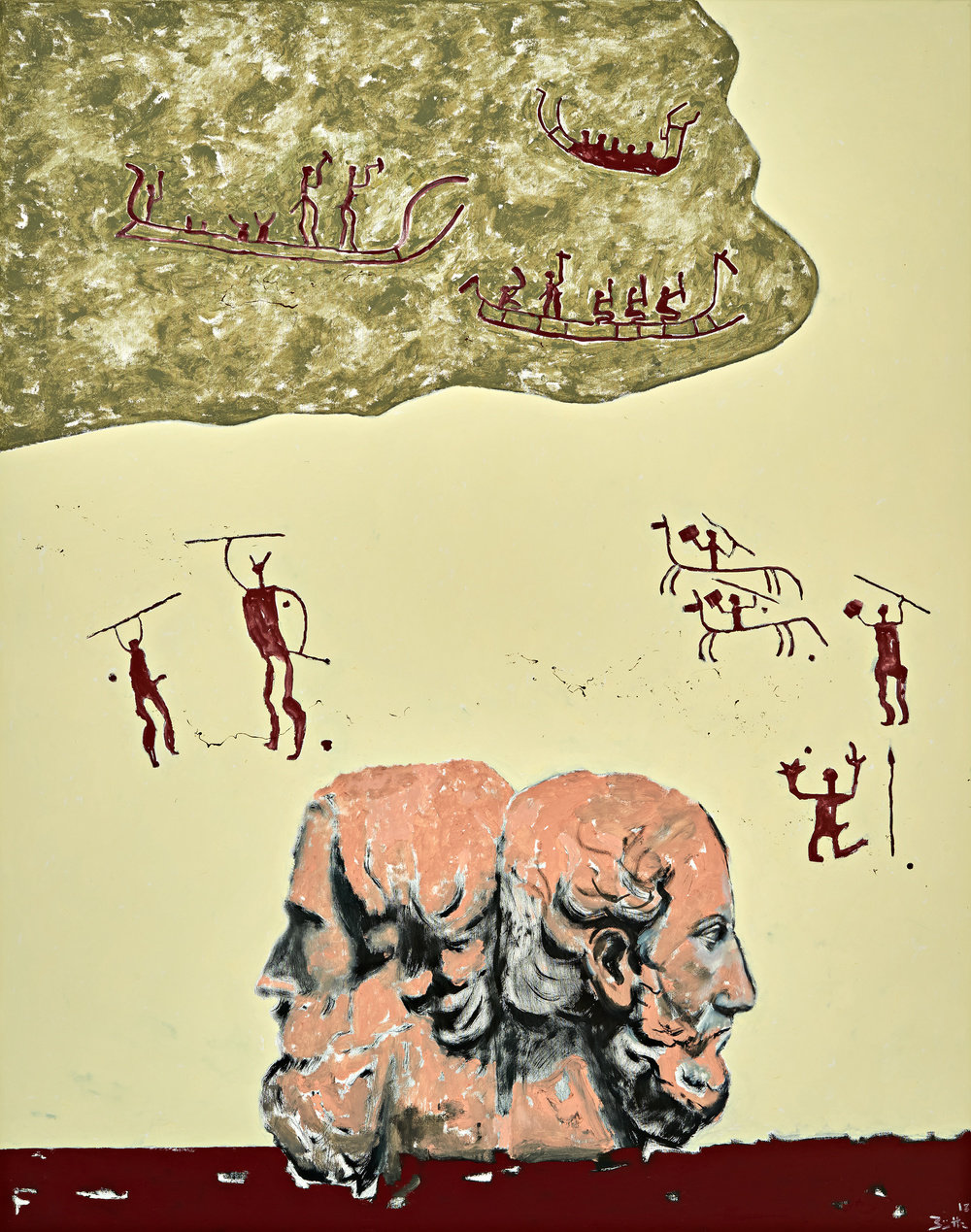

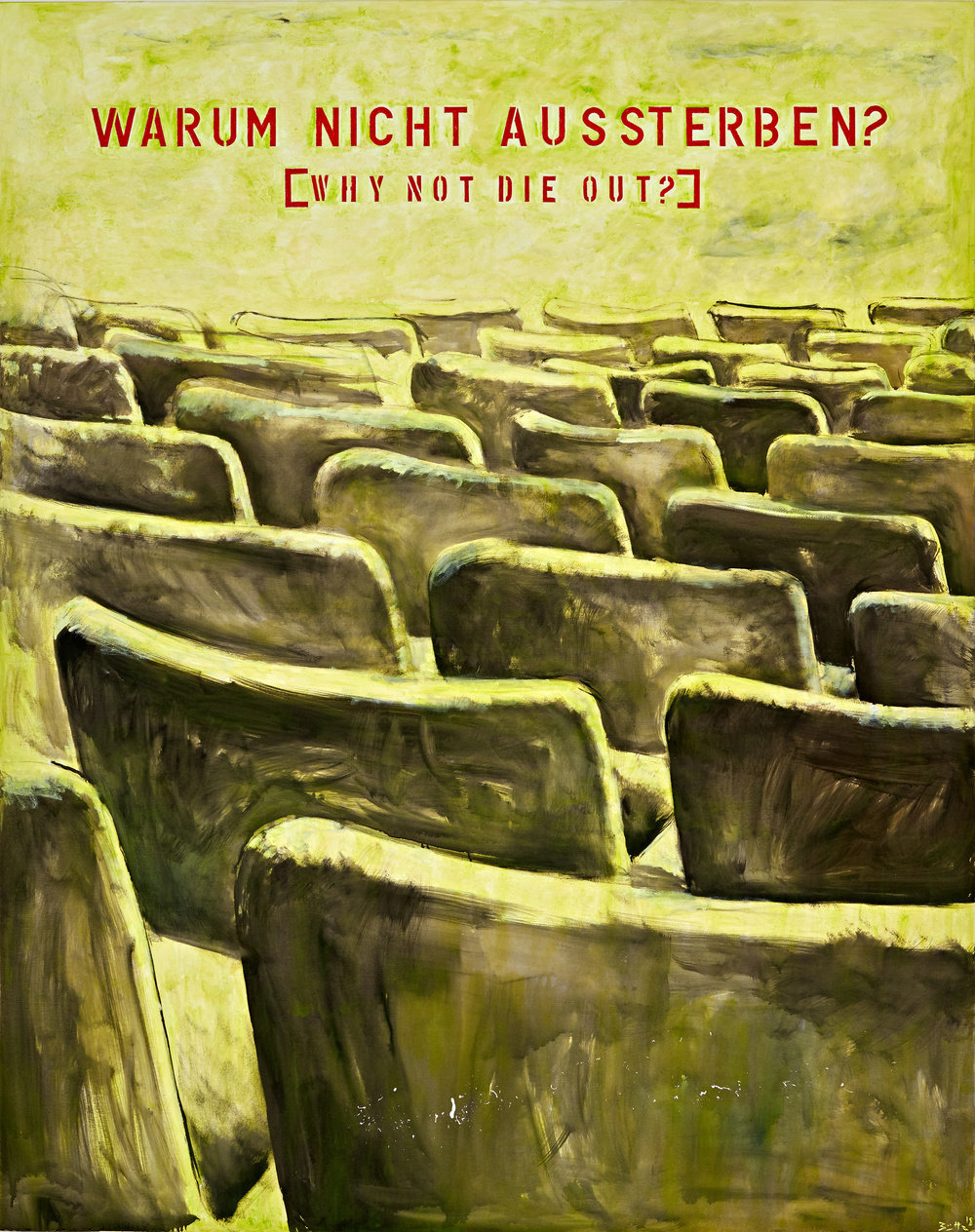

It is the artist’s first show with the gallery to integrate these various tendrils of his practice in a more detailed illustration of his broader conceptual concerns. If we consider Büttner’s production to be concerned with his refraction of a continuous information flow—from ancient history and philosophy to current events to goings on outside his studio window—Something very blond comes to town expresses this fact through a variety of source materials and approaches. The oil paintings tackle life’s big existential questions via an acute art historical lens, while the sculpture and thrift store paintings rely on chance encounters with readymade materials to provoke a narrative. Together, the works establish a wry worldview that displays a professorial depth of knowledge and a comedian’s dark sense of humor.

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalog with an essay by Kenny Schachter, excerpted below.

Werner Büttner was an early hero of mine, not merely for the fact we both studied law before lapsing, nor because of his amazing late 1970s collaborations with Martin Kippenberger and Albert Oehlen, but rather due to his exploits as a key participant in a group of major postwar, post-Beuys-Richter-Polke German artists. Don’t be fooled by his avowed dismissals of technical aptitude—Büttner’s brand of casual self-deprecation and nonchalance masks an artist relentlessly at it.

When he began making art in earnest in the late 1970s, Büttner said he and his pals were trying to expand the range of painting motifs, though many efforts “failed in such a venerable medium.” Yet you get the impression that Büttner was, in essence, cultivating imperfection. He wanted to see how lowbrow and dumbed-down he could go, testing timeworn notions in art. His conscientious subversiveness was as much an expression of disparagement as awe—pissing on painting while venerating it. Something of the wordsmith, Büttner’s titles—by turns sardonic and questing—are pared-down poems for the short-attention-spanned.

Büttner has always worked in series, though you would be hard-pressed to identify or discern too many similarities between the related works; that’s because they are grouped by loose, self-imposed operational parameters, rather than unflinching, formal constraints. Thrownness is philosopher Martin Heidegger’s theory that we are unwillingly (and unwittingly) thrust into a world fettered as much by social convention as familial chaos before we’re even out of diapers. Büttner’s exit strategy for this morass, which sees us behind the eight ball from the start (which formed the basis for his “On Thrownness and Entanglement” series) is humor—a mordant, exasperated, resignation of the absurdity of it all.

-Kenny Schachter

Works

Press